Please forgive my very long hiatus. I try to post on a fortnightly or, failing that, monthly basis, but I ended up having a very busy month, particularly with work, so this fell by the wayside.

Part of the slowness may also be due to a certain amount of trepidation on my part. I realised, in the process of writing this piece, that it ends up going into quite personal territory. I’ve wondered how much of that to cut and how much is interesting to the reader rather than me navel-gazing. That bothered me less when I was spotlighting my younger self, because it’s very easy and funny to clown on our teenage selves. There’s also a fear of self-indulgence: is this about music or is it about me? If the latter, the classic Irish thought comes to mind: why would anyone be interested in reading about me? I think it’s best to let the reader be the judge of that, so no worries if you don’t feel like reading all about my twenties.

In writing this, I also decided that there will not be a part 3 to the series, or at least not for a while. I think I need to let the years percolate a bit before I select any more albums that are definitive of these times of my life. I don’t want to prematurely editorialise my life and to end up selecting albums that are influenced by how I want to be perceived. I think, in a few years, I can look back at my late twenties with a more distant eye and see what emerges. Right now, it’s still too close to call.

Thank you for coming to read this, and I invite you to subscribe below if you would like my new posts linked straight to your email.

So, here they are. The three most important albums in my personal development from 2014 to 2019 or thereabouts. They’re actually all quite sad, and so was I at this time. But I was also having the most silly, youthful fun of my life.

Neutral Milk Hotel – In the Aeroplane Over the Sea (or how “cool” can be so cool that it comes full circle and is unspeakably naff)

Oh, how delighted I was, a newly minted young adult, to find myself liking something that was undeniably cool. April Ludgate, fictional cool girl, was into this album. And how delightful, to have a cool album actually be interesting, and fun to listen to, and sad, and evocative…

This might be an embellished memory, like the one where my brother introduces me to Green Day. However, as I remember it, I was on campus in second year of university in Galway. I was at Smokey’s café on the concourse, meeting one of my best friends for coffee between lectures. He bounded up to me, unusually energetic, and sat down. As if I were a Hollywood exec and he a screenwriter, he began to pitch me In the Aeroplane Over the Sea by Neutral Milk Hotel.

“So it has hip hop bagbpipes and it’s about the singer being in love with Anne Frank,but not really like that, it’s more of an ideological thing, and growing up, and death, and puberty and being in love…”

Sold!

The next time we met, I was ready to discuss ITAOTS. Anyone overhearing our conversations about this album would have found us highly pretentious, but we had long decided that, in our friendship, we would lean heavily into being pretentious twats. We had always enjoyed discussing literature, and if we sounded like we thought we were very smart, it’s because we really did think we were.

ITAOTS really is an amazing album. It opens with acoustic strumming and the words “When you were young you were the king of carrot flowers,” whatever that means. Whatever it means, I know how it feels. The song is in the second person, narrating from the perspective of “you”, inviting you to accept the words that follow as yours, and implying a universality to the songs on the album.

It’s often considered to be an album about Anne Frank, and Neutral Milk Hotel frontman Jeff Mangum’s obsession with her. He has said that ‘a lot of the songs on this record are about Anne Frank”, and in the same interview (“Dropping in at the Neutral Milk Hotel” by Mike McGonigal) discusses how he read The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank and spent the next three days crying.

For anyone who has not read The Diary, here is a brief description. It is the real diary of Anne Frank, who was murdered by the Nazi regime at the age of 15 at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. It follows her life from the age of thirteen, when she is given a diary for her birthday. Shortly after that, she goes into hiding with her family in a secret annexe in Amsterdam. Her last entry is 1 August 1944, after which they were discovered. The only surviving family member was her father, Otto Frank, who then published her diaries in 1947.

Back to the album. In ‘Holland 1945’, the narrative voice is in love with her: “The only girl I’ve ever loved/Was born with roses in her eyes/But then they buried her alive/One evening 1945/With just her sister at her side”. This, alongside the strange and sometimes sexual lyrics that recur throughout the album, though never directed at or directly about Anne Frank (“Sweet communist, the communist daughter/Standing on the seaweed water/Semen stains the mountain tops”), has invited criticism of the lens through which Mangum seems to see her.

We’ll look a bit more at the book which inspired Mangum before we litigate this criticism.

The Diary of Anne Frank works on two levels. Reading it if you have ever studied literature causes you to see things that you think of as foreshadowing (when Anne thinks someone sees her through the window), or character development (her growing understanding of her mother and her sister, Margot). But then you remember that this is not foreshadowing or character development – this is life. This strange feeling seems to suggest that there is sense to life, and art imitates it in its forms. Real life holds portents or signs, just as fiction has foreshadowing. That feeling that there is a sense to life shudders to a halt as the diary ends and you remember that this person’s right to express themselves, to create, and finally even to life, was wrested brutally from them. You then mourn Anne, and suddenly, dizzyingly, you are compelled to consider that every person murdered by the Nazi regime had a life and inner voice as real and complex as Anne’s. The magnitude of human suffering stuns you.

The other level on which it works is that it is, as its title says, the diary of a young girl. Reading it at her age, I related to her friends and frenemies, her crushes, her fights with her mother and sister, the stress and mystery of the onset of puberty. That the writings of a young Jewish girl in the Netherlands in 1945 could resonate with a young Catholic girl in Galway in 2005 feels remarkable.

So, what is with Jeff Mangum’s weird declarations of love for her, and is it bad? Your mileage may vary on this one.

It’s worth noting to those who may not be very media literate that Mangum can write a song, as a writer can write a novel, without being the same person as the narrator. In fact, as we saw in the first lines of the album, the narrative voice is handed to the listener (“When you were young…”).

I think Anne Frank’s story serves as an emblem for the album, rather than being the literal focus. She’s never named explicitly, nor is she the only subject. Mangum’s lyrics span lifetimes (“now she’s a little boy in Spain/Playing pianos filled with flames”, “And one day in New York City, baby, a girl fell from the sky/From the top of a burning apartment building 14 stories high”), different stories threading in and out.

The parts about love are not about Jeff Mangum being in love with Anne Frank, they’re about being young, and the perseverance of youth against adult horror thrust upon it. “And your mom would stick a fork right into daddy’s shoulder/And dad would throw the garbage all across the floor/As we would lay and learn what each other’s bodies were for.” What seems to be constant is the album’s love of life itself, even among pain and destruction. I see it as a mourning of young lives cut short while celebrating the vitality and meaning of their time on earth.

The image that seems to confirm this is the last verse of ‘Holland 1945’: “And it’s so sad to see the world agree/That they’d rather see their faces filled with flies/All when I’d want to keep white roses in their eyes.”

The world remembers the sadness and horror, the “faces filled with flies”, but Mangum is advocating here for remembering the life and beauty, the “white roses in their eyes”. Both are important to memorialise, but ITAOTS is focusing on life, youth and potential, with sadness and loss as ways to emphasise the tenacity of hope.

Those are my feelings about the album. It’s complicated and weighty, and makes you think about bigger things.

I suppose the praise and cult status it gained in the decades following its 1998 release (such that two college students in 2014 felt very cool for liking it) also caused it to become a meme. On subreddits like r/indieheadscirclejerk, the tendency to put this album on a pedestal is lampooned.

While the album has some sincere detractors, the memes about ITAOTS is more about the sort of “flex” of saying you like the album. Listing the album as one of the best has become almost cringe. It has become a kind of shorthand for the type of person who wants to wants to be seen to like something complicated and high-falutin’.

For my part, I definitely did feel super cool and smart for liking this album, until the memes came. However, the album is legitimately good enough that this does not matter. I feel cooler sincerely liking something than I ever did trying to like the right things.

To anyone who thinks In the Aeroplane Over the Sea is pretentious, I would invite them to try to enjoy the entirety of Neutral Milk Hotel’s earlier album, On Avery Island. The greatness (‘Song Against Sex’, ‘Naomi’ and ‘Where You’ll Find Me Now’) is balanced by the absolute what-the-fuckery that is ‘The Pree Sisters Swallowing a Donkey’s Eye’.

The Smiths – The Queen is Dead (or my leaning in to truly experiencing emotion in all its horrifying, embarrassing glory)

In 2016, a strange thing happened. Having broken up with my boyfriend of four years, I was faced with a new enthusiasm for music.

I had certainly enjoyed music in the preceding four years. Only, it had to be music that didn’t cause me to think deeply about my feelings. I didn’t really know that I was doing this until after the breakup. Through no fault of anyone, the relationship had been flawed and I had been trying to avoid facing this truth for a long time.

In the Aeroplane Over the Sea was probably the only album I was really into during that time. I was also very into Kesha and songs from musicals (I’m really all over the map). But music about heartbreak or true love, or anything that threatened to pull me towards introspection, I pulled away from.

One dark November night, heading home from my then-boyfriend’s house, I passed a busker playing ‘Father and Son’ by Cat Stevens aka Yusuf Islam. He sang “I know I have to go”, and it unexpectedly penetrated my no-introspection armour. I began to cry. I knew I had to end things.

After the breakup, I finally shrugged off my mantle of denial and began feeling EVERYTHING. Including a giant crush on a colleague from the shop where I worked.

He had a really nice way of introducing me to new music. Rather than say “You should listen to Deftones”, he’d say “What do you think of Deftones?”, seeming to assume that I was already familiar with their oeuvre. When he asked me about my feelings for The Smiths, I didn’t directly lie, but I phrased my answer carefully.

“I really like ‘There is a Light’ and ‘Asleep’, and I also think ‘Some Girls are Bigger than Others’ and ‘This Charming Man’ are great”.

Translation: “I have listened to exactly four Smiths songs, and I have listed them herewith.”

Well. As my crush grew, so did my love for The Smiths.

To anyone who knew me at this time, I’m very sorry. It’s like when I got really into Monty Python as a teenager. In every conversation, I found a way to quote a Smiths song, or to tell someone at length about Morrissey’s lyrical genius. All I did was reference the Smiths for about two years.

My entry point to a full blown Smiths obsession was The Queen is Dead. It has everything you want from The Smiths: petty grievances (‘Frankly Mr Shankly’), the dark creeping sense that nothing will ever work out for you (‘I Know It’s Over’), grandiosity masquerading as self-effacement (‘Bigmouth Strikes Again’), brazen pretention (‘Cemet’ry Gates’), camp (‘Vicar in a Tutu’) and probably the greatest anthem for awkwardness ever in ‘There is a Light that Never Goes Out’. There’s only one song that I don’t love on the album, and it may actually be the only Smiths song that has never hit for me at all (I’m someone who sincerely likes ‘Golden Lights’), and that’s ‘Never Had No One Ever’ which feels redundant and almost parodic (but not in a fun way) right after ‘I Know It’s Over’.

Re-reading the above paragraph, it sounds like I’m roasting the Smiths. That’s only because I relate so strongly to their work that I cannot help but imbue my writing about them with the same deprecation as I would use on myself.

Let me be clear: this album made, and still sometimes makes, me feel as if someone has scraped out the saddest corners of my soul with the fears I’d never dared to speak into reality, as if someone has found their way into my memories, as if someone knows the parts of me that are mean and defensive, and witty and smart, and then hopped into a time machine and recorded this album in 1986.

It’s just so funny and profound and smart-arsed. Favourite lyrics include:

“So I checked all the registered historical facts/And I was shocked into shame to discover/How I’m the 18th pale descendent/Of some old queen or other” – ‘The Queen is Dead’

“Frankly Mr Shankly, since you ask/You are a flatulent pain in the arse” – ‘Frankly Mr Shankly’

“It’s so easy to laugh, it’s so easy to hate/It takes guts to be gentle and kind” – ‘I Know It’s Over’

“A dreaded sunny day, so let’s go where we’re happy/And I meet you at the cemetery gates/Keats and Yeats are on your side/While Wilde is on mine.” – Cemet’ry Gates

“Sweetness/Sweetness, I was only joking when I said/I’d like to smash every tooth in your head” – ‘Bigmouth Strikes Again’

‘And in the darkened underpass/I thought Oh God, my chance has come at last/But then a strange fear gripped me and I just couldn’t ask” – ‘There is a Light that Never Goes Out’

The elephant in the room of any contemporary discussion of the Smiths is that Morrissey is horrible. He is mean, xenophobic and moves further and further right-wing as the years pass. If it is any comfort, he is not exactly winning any hearts and minds or attracting anyone to his worldview. He mostly just maintains a blog where he complains about everything.

Some people say it’s hard to believe he became this person, but I think Morrissey is what happens when you nurture a kind of internal otherness that rejects others before they reject you. His lyrics speak to sad parts of ourselves, or angry parts, or the l’esprit d’escalier feeling of thinking of the perfect insult long after you have the chance to use it. There’s liberation in that as a pressure release, but it’s no way to live.

The crush on the colleague, coming as it did alongside me becoming one giant nerve ending in the aftermath of my numb years, ended up being confusing and heartbreaking. That heartbreak though, it felt amazing. Every subsequent heartbreak, I would listen to ‘I Know It’s Over’, a kind of theme song for my disappointment. So self-indulgent of me!

But heartbreak is something I always remember to indulge in, a little bit, as a treat. I think of this particular heartbreak with fondness. It was so much better than feeling nothing at all.

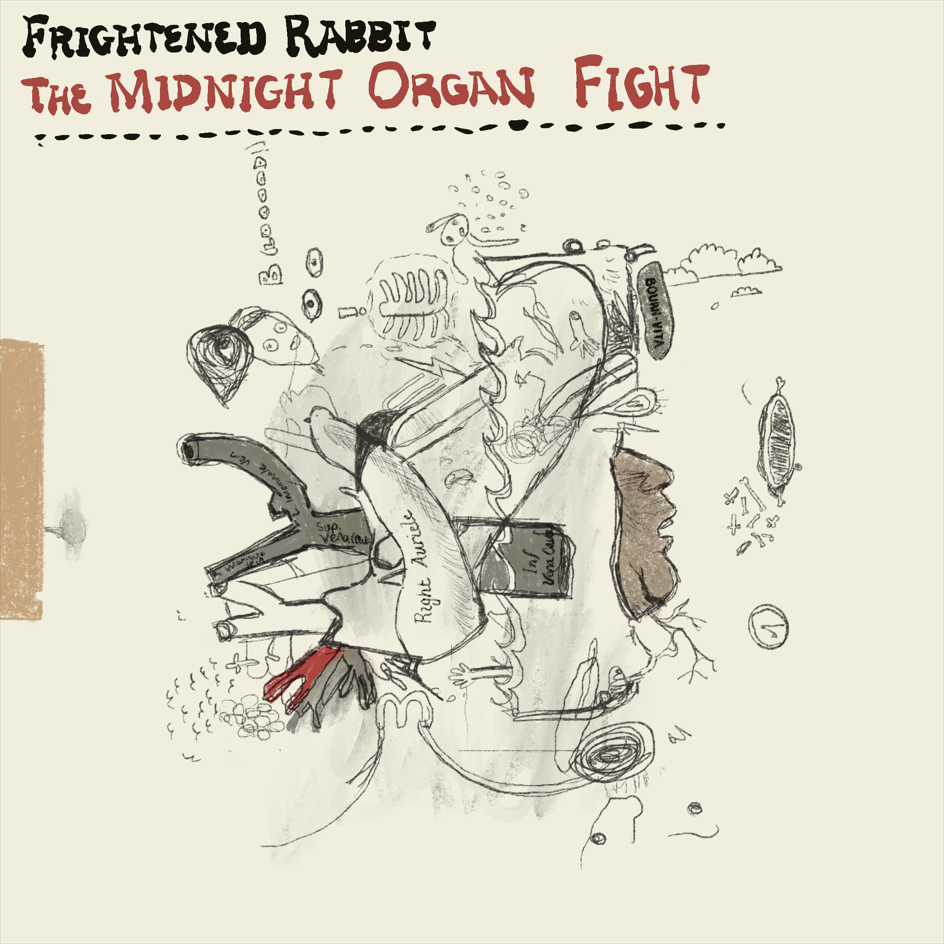

Frightened Rabbit – Midnight Organ Fight (or when heartbreak gave me the album with which to get over it)

I often look at my music taste in my twenties and realise how often I was influenced by the men I dated or was otherwise close to. Each of these entries is an album that a man “gave” me (of course, not literally, the cheap bastards). There’s probably something worth analysing in that (and to be fair to me, I have analysed that), but I do quite like the image of myself as a kind of palimpsest, becoming cooler after every dude I went out with. Engulfing and digesting their interests, expelling the ones that don’t resonate with me (I’m sorry – Car Seat Headrest has never hit for me, men) and keeping the things I really loved.

I had a brief relationship (what we now reductively call a ‘situationship’) in my twenties that had no right to be as influential as it was. By our third date, I had fallen hard. To be fair, our third date was a three-county, three-night, attending-his-friend’s-wedding extravaganza. By that stage of my life, I’d had a few painfully non-committal entanglements in the preceding years, and I thought the wanting-to-bring-me-to-a-wedding factor signalled an openness to a relationship. Rookie mistake, says every woman who was single in their twenties as they read this.

It was late the night of the wedding, in the hotel room, that he said “If I wanted a girlfriend, it would be you.” A dizzying, “here we go again”, end of a sitcom episode feeling overcame me . I imagined ‘I Know It’s Over’ would play at this point in a tv adaptation of my life, or perhaps be the theme tune.

By the morning, I had decided that I would keep seeing him, in the hopes that he would change his mind. He didn’t. I treated every date like an audition to be finally accepted as a girlfriend. He was probably in disbelief at how handy it was to have the Girlfriend Experience, minus any commitment or responsibility.

The relationship ended, a good bit after it should have, when he suddenly became very cold. Though harsh, it was helpful, because there wasn’t much that would have dissuaded me from continuing to date him otherwise. I clearly was willing to tolerate a lot of confusing treatment. Without this definitive end, I probably would have just kept on hoping that I would one day pass the test.

I later learned that “If I wanted a girlfriend, it would be you” was something he said to multiple women, often in very similar circumstances. It seems in his mind it was a very neat disclaimer, like at the end of a radio ad: “This man does not claim any responsibility for love that may or may not result from spending 72 hours in each other’s company. Any resulting psychic trauma should be directed to your GP for appropriate treatment. This man is regulated by the Central Man Regulator.”

Anyway, the guy had great music taste. Every time I fell in love with someone back then, my Liked Songs on Spotify quickly filled up with stuff they showed me. It’s to the extent that I can track who my love interest was as I scroll down through the list.

He introduced me to an album which ended up being the soundtrack of my getting over him: The Midnight Organ Fight by Frightened Rabbit.

Discussion of this album will also involve discussion of suicide, so trigger warning for that. I’ll add a little paragraph for when discussion of suicide concludes and when you can pick back up reading, if you choose not to read about that.

The Midnight Organ Fight by Scottish band Frightened Rabbit is an album with cult status, just like ITAOTS. It’s also got (to me) a deceptively twee cover. Indie albums with covers like that never really hit for me, but I was willing to give it a try.

Added this after I drew the cover to head this section: I was wrong, it’s actually full of details I never took the time to pick out before. It’s quite morbid but with a lightness of touch that matches the tone of the album pretty well. I think I actually just don’t like design from this time very much, and at a glance this one seems fairly typical of the era. It really isn’t, though,

It turned out to be anything but twee. It’s a collection of songs about depression, a disintegrating relationship, suicidal ideation and legacy. The album is wallowing, while making grim fun of itself for wallowing: “You must be a masochist/To love a modern leper/On his last leg” shouts Scott Hutchison on the album’s opening track, ‘The Modern Leper’. His voice is strong and emotive, masculine and vulnerable.

It’s also an impressive album, musically. It was only years later, listening to Billie Jo Spears’ ‘Sing Me an Old-Fashioned Song’ that I realised that Frightened Rabbit use the same strumming intro as a kind of reference to it in ‘Old Old Fashioned’. There’s a galloping, roaring energy to ‘Modern Leper’, ‘I Feel Better’, ‘Fast Blood’ and ‘Head Rolls Off’ which marries with some of the heaviest lyrics I’ve ever heard. The sound feels anthemic, triumphant, helping to lift the weight of the words and ideas within.

My favourite track is ‘Poke’. In it, Hutchison sounds raw, exhausted. It’s about a long-term relationship that has totally broken down. In it, he asks for physical pain to take the place of the emotional numbness: “Poke at my iris/Why can’t I cry about this”, and incorporates pet imagery to show how the companionship has been reduced to being akin to a useless cat or a dying dog rather than a life partner: “I might never catch a mouse/And present it in my mouth/To make you feel you’re with someone/Who deserves to be with you,” and “Why won’t our love keel over/As it chokes on a bone?/We can mourn its passing and then bury it in snow.”

There’s one powerful, beautiful image that shows the final remnants of their love: “But there’s one thing we’ve got going/And it’s the only thing worth knowing/It’s got lots to do with magnets and the pull of the moon.” This cosmic connection, almost twinning, now reduced to “I’d say she was his sister, but she doesn’t have his nose.” Witticisms like that, rather than breaking the tension, evoke the rueful laugh that one coughs out between sobs.

‘Head Rolls Off’ is particularly interesting. Firstly, because it starts off with the incredibly funny line “Jesus is just a Spanish boy’s name”. Irreverently, he goes on to talk about how it’s not morbid or unkind to be flippant about death, seeming to find comfort in pragmatism: “it’s not morbid at all/Just that nature’s had enough of you”. He invokes religious imagery again: “I believe in a house in the clouds/And God’s got his dead friends round/He’s painted all the walls red/To remind them they’re all dead.” It seems to make gentle fun of the idea of the traditional idea of heaven, that all of God’s preferred pals would be invited to some undead dinner party. The song seems to suggest that the afterlife that we long for could instead be the impact we leave on the world: “You know when it’s all gone/Something carries on […] While I’m alive, I’ll make tiny changes to Earth.” Hutchison sings about the cyclical nature of life: “When my blood stops/Someone else’s will thaw/When my head rolls off/Someone else’s will turn/Mark my words, I’ll make changes to Earth.”

Hutchison died by suicide in 2018. His friends and family founded a charity in his honour called Tiny Changes, which helps to provide mental health support to young people in Scotland. The cult status of Midnight Organ Fight also led to a cover album, which was originally set to release before Hutchison’s death but instead came out in 2019 featuring Biffo Clyro, Daughter, Aaron Dessner, Julien Baker and Lauren Mayberry, among others.

End of suicide trigger warning here. If anyone needs resources for support after reading about the topic, the HSE lists some resources here.

With all of that in mind, it feels small and petty to connect it to my little heartbreak. However, the album’s sense of making peace with doom resonated with me after the end of my relationship with this person. Looking back, all I saw were times I could have ended the relationship earlier to avoid the pain, but instead I kept going back in the hopes that the situation would change. This album helped me accept the fact that I’d treated myself so poorly.

It also gave me a new lens through which to view the ex-not-boyfriend. Rather than some amazing, infallible cool guy, the ‘modern leper’ image offered an alternative perspective: “Is that you in front of me/Coming back for even more of exactly the same/You must be a masochist/To love a modern leper on his last leg.” Yes, I was returning, time and time again, to be rejected and humiliated, but he probably had some bad self-esteem stuff going on too. It’s not like he was living the dream, with me the pathetic one. It helped me to take him down from the pedestal where I’d placed him, which did a disservice to both of us.

The gallows humour of the album was also really resonant for me, because, Jesus Christ, this situation had some very funny bugs. This guy was in a band, and fortunately I never listened to them while we were seeing each other, because by all accounts they’re really good. I can only imagine how much harder it would have been to get over it had I liked the music. After we ended, the band took off, and suddenly everyone I knew was talking about them, right when I never wanted to be reminded of his existence. The mania hit its peak when he featured on a LITERAL billboard was erected metres from my apartment. I had to laugh because, Christ alive, I was really not being allowed to forget this man.

So, yes, my funny doomed little horror of a relationship ended, but my love for this album full of its own doom, humour and horror lives on. I fulsomely thank this man for showing me Midnight Organ Fight, as well as some great songs. As for his own music, I’ve still managed to avoid it.

Thank you for reading! Please leave a comment if you have any suggestions for my next post, otherwise I’ll subject you to one of my personal obsessions. Which you’ll probably enjoy too!